How do we preserve and interpret the historical record in a digital age? Traditionally, archivists collect and preserve historical sources, historians interpret them through books or documentary editions, and publishers distribute them. Today, historical sources that once would have been only accessible in private collections or the archives, are now shared widely online, but without the context or editorial framework that would allow those sources to be used in the classroom, research, or public history.

In the Department of History, SourceLab was created in 2015 by professor John Randolph to tackle the unique challenges of preserving and interpreting the historical record in the digital age.

“Now we're in a world where everybody's a publisher, and yet there's no place that teaches publishing skills, and it seemed to me that this was a place where we, as historians, both had a particular responsibility and also particular opportunity to train ourselves and to develop skills which could be quite useful,” said Randolph.

SourceLab started with a class that taught undergraduates how to create digital documentary editions of historical sources like letters, films, music, pamphlets, and other artifacts. Ten years later there is a graduate seminar, a journal where students can publish the documentary editions they produce, and weekly meetings (called SourceLab Mondays) where students and faculty across the university can convene to explore topics in the digital humanities.

In the undergraduate course, HIST 207: Digital Documentary Editions, students work in groups to create documentary editions of historical sources that have been suggested by clients who want to use them in their scholarship or teaching.

In the process, students learn about copyright law and intellectual property rights, the ethics of publishing a historical document, how to provide the contextual information the source’s audience will need to understand it, and how to use digital publishing tools like Scalar (an open source, web-based publishing software that allows you to create multi-media online publications).

Students can then submit their edition to the editorial board of the journal, also called SourceLab. After a documentary edition passes a rigorous peer review process it’s published.

Editions include:

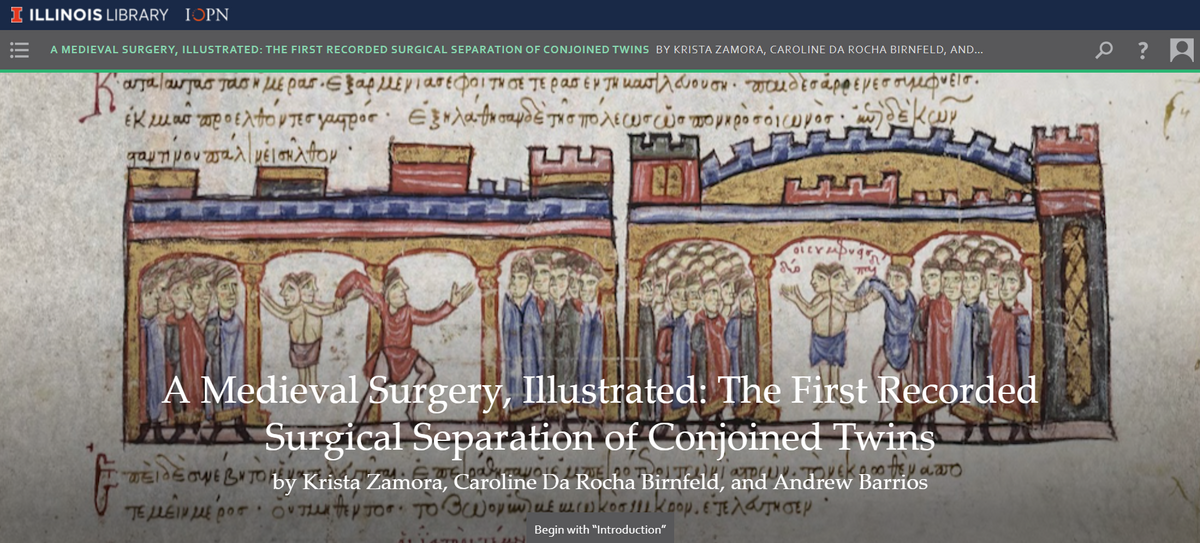

- An example of Byzantine surgery to separate conjoined twins preserved in a 12th-century illustrated manuscript by Krista Rae Zamora, Caroline Da Rocha Birnfeld, and Andrew Barrios.

- The 1946 film created by Disney and the Kimberly-Clark corporation The Story of Menstruation by Mariah Mendes Schaefer.

- An analysis of six early songs of the Russian punk group Pussy Riot by Jaime Hendrickson.

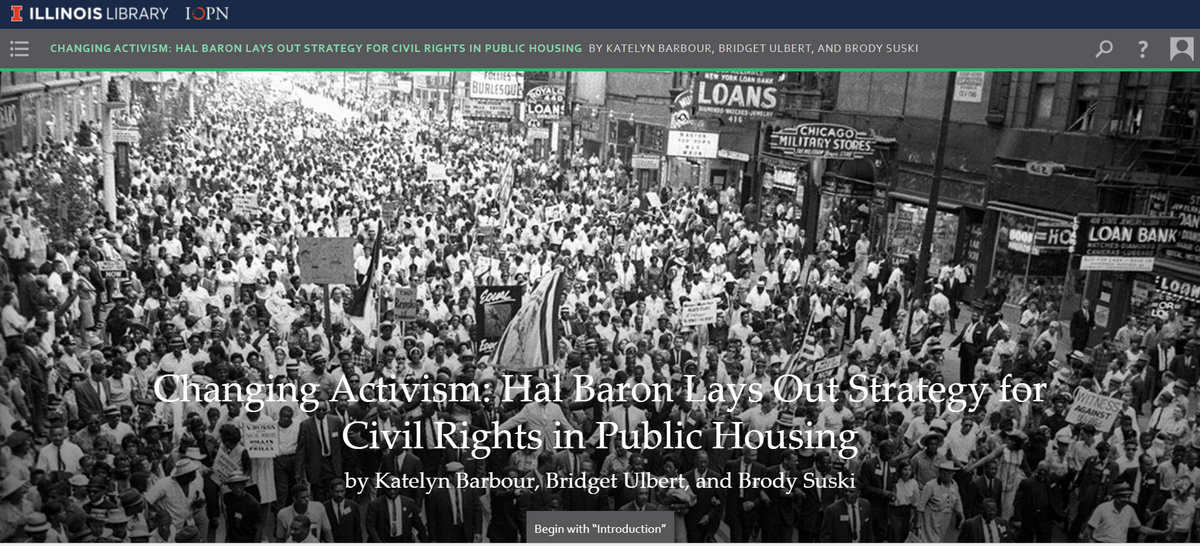

- Harold “Hal” Baron’s memorandum outlining a strategy for ending housing discrimination in Chicago using the Civil Rights Act of 1964 by Katelyn Barbour, Bridget Ulbert, and Brody Suski.

Katelyn Barbour, a senior history and gender and women’s studies major, has been involved with SourceLab since she took HIST 207 in her freshman year. She’s served as an editorial assistant, created a digital edition, and now serves as the managing editor of the journal.

Barbour said the digital publishing skills she’s learned through SourceLab will be a valuable asset to her when she begins her master’s in history at the University of Chicago in the fall.

“It gave me the foundational building blocks for figuring out what research looked like on a smaller scale, but with a really specific focus,” said Barbour.

Barbour said she has also benefitted from exposure to other digital humanities tools through her involvement with the collective’s SourceLab Mondays.

What started as Zoom meetings during the pandemic has grown into a regular meeting every Monday in the Paul M. Lisnek Hub in Lincoln Hall. The meetings are a mix of collaboration sessions, teaching sessions on digital humanities tools, and open mic sessions where people can present projects they’ve been working on.

SourceLab Mondays are organized by Richard Young, a history graduate student and research assistant for SourceLab. His research uses AI to examine Coca-Cola advertisements between 1890 and 1930 to explore the history of happiness and how advertising influences the way we feel. He said the community he has found in SourceLab has enriched his experience in the department and has helped him cultivate an interest in the digital humanities among his peers.

“I very much like the idea of using computers to help with my historical work, and I've found it's a hard sell to a lot of historians. Finding a community where there’s interest in that has been very helpful and very valuable,” he said.

Young’s work has helped expand the collective to provide a space where students and faculty can explore digital humanities tools. He has led workshops on tools like ArcGIS Storymaps (a software that allows you to create interactive maps) and recently presented at Illinois State University, with fellow collective member Owen Monroe, on software that SourceLab has been developing called MinDoc. MinDoc will allow researchers to easily create static webpages to share a project through the website builder GitHub, without any knowledge of coding.

Randolph is proud of the way that SourceLab has expanded over the years and the connections it has created across the university. He hopes it continues to grow and provide a space to experiment with new forms of scholarship.

SourceLab has also given graduate students an edge on the job market and is influencing programs at other institutions. Randolph said several recent PhD graduates who served as instructors for HIST 207 used their teaching material in tenure-track job applications and are now implementing SourceLab inspired classes at their institutions.

Though there are programs at other universities where students can gain experience in digital documentary editing, Randolph said that SourceLab’s approach remains unique.

“There are a number of initiatives where students work on some large, ongoing project that's publishing the papers of a famous person, or something like that. But we're trying to do something different. We're trying to find ways that students can help teachers, researchers, and the public at large use materials that have appeared online, but without any context or editorial framework. Our students pick the clients they work with, and produce small-scale editions targeted to specific purposes. It's kind of like a triage service for the new historical record. And so in that sense, I think we're still innovating in the digital editing space,” he said.