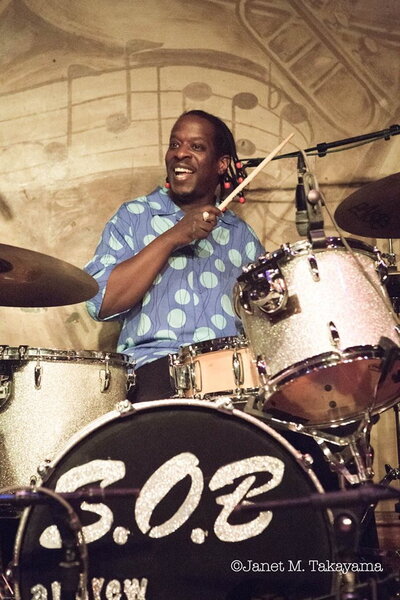

When Andrew Thomas, a former professional blues drummer, decided to study history, it was during the pivotal summer of 2020. The Covid-19 pandemic had shut down music venues across the world and put his 20-year career as a blues musician on pause.

Thomas had traveled the world and played with some of the biggest names in blues and roots music. He was a 2019 Blues Music Award Winner and wrote the book You Got the Gig, Here’s How to Keep it: A Working Musician’s Model for Success. Instead of going on tour that summer, he spent his time creating drumming tutorials and producing music.

That summer, the U.S. was also in the midst of a reckoning with police brutality against African Americans after the death of George Floyd. Thomas was deeply affected by the violence against Floyd and so many other Black individuals. After he saw a racist post from white fans about the killings, and the lack of empathy from the white drumming community after the death of Corey Jones, a drummer who was killed by the police, he became disillusioned with his white fanbase.

“That's when the axiom they love our rhythm but not our blues became really true for me,” he said. “They want to look at my YouTube channel and they want to look at my Facebook channel and all of this to forget about, you know, what they consider politics,” he said. “But it's not politics for me. It's my life. My life is on the line.”

While he was grappling with these events, he ran across a recording of a panel featuring prominent Black intellectuals and activists including Angela Davis, Huey P Newton, and Fred Hampton. He was struck by how their 1973 conversation about police brutality, injustice, and poverty could have easily taken place in 2020.

“And the thing that really caught my eye is they all could talk about these problems without swearing, without losing it, without crying. No emotion. They can have adult conversation about some of the most horrific things that we see every day. And I say, I want that. I want to be able to understand race. I want to be able to understand problems. I want to be able to disseminate information without using swear words, without breaking out into a cold sweat, without throwing a shoe at my television. You know, I want to be able to calmly speak and use my brain to understand what I'm seeing. So that was the catalyst, you know, to just go back to school. And I'm happy, it’s the best choice I've ever made.”

Thomas has always loved Black history and minored in African American studies for his bachelor’s degree at Western Illinois University. Learning about great African empires in Mali and Songhai, and leaders like Queen Nzinga in Angola and Queen Candace in Ethiopia, were exhilarating experiences for him, especially after hearing so much about European rulers and history during his K-12 education.

“I've always just loved you know Black history because of the feeling that Black history provides for most Black people . . . There are all these great, great civilizations, and once we find out about these things, the first thing that happens is we get a great rush and great emotion and we feel we’ve unlocked this consciousness,” he said. “And then once we’ve unlocked these things, we want some resistance, and we want to learn more about resistance and how can we fight the man and how can we get back some justice? And how can we be active? But once you unlock all these emotions, you're going to have to get yourself some education. You're going to have to do some reading and studying, and you're going to have to understand how humans relate to one another because Black folks aren't the only people that are suffering or have been through the history of suffering. But we just know we're suffering right now. So during the summer of 2020, it was just coming to fruition coming to, you know, to the head. And I decided to go back to school and study history.”

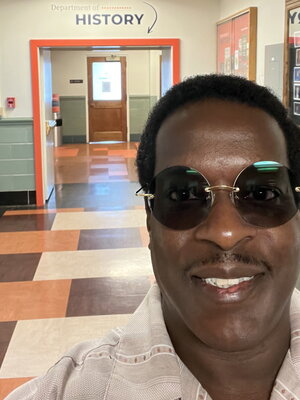

After completing his master’s degree in history at Illinois State University, he entered his PhD program in history at the University of Illinois, and just finished his first year in the program. His advisor is professor Sundiata Cha-Jua, who has become an important mentor for Thomas and encourages him to pursue the connections in Black music across the African diaspora.

Thomas’s first research paper focused on identifying Africanisms in blues after he realized that most books on blues start the narrative with slavery. Africanisms are characteristics of African cultures that can be traced through the cultures of the African diaspora. One example of an Africanism in blues music is the phrase mojo, which can be traced back to pouches worn around the neck by the Bakongo people from the Democratic Republic of Congo.

“Within this mojo pouch, you know, there might be some black dust from this riverbank, and a little cat bone, and all these little mystical little things and tea leaves, and herbs and spices,” he explains. “And this little pouch is bound up in this tight leather. And you never take it off from around your neck. As long as you believe in this little pouch, you have good luck. Well, this stuff is in blues and a lot of blues lyrics, a lot of blues music, even casting good and bad spells from the mojo is in these blues lyrics.”

Writing the paper was a foundational scholarly experience for Thomas and taught him the importance of tracing African American culture back to Africa.

“Identifying these Africanisms within the music was a really eye-opening study for me because it proves again that African, Black folks, we had a long history before chattel slavery and in order to study anything concerning Black people it starts with Africa . . . If you ignore Africa and you start with the United States, you’re going to miss something that’s intrinsic to why we do things that we do today,” he said.

Thomas is also the chairperson of the Bloomington-Normal Black History project, a group that was started in 1981 by Illinois State University professor Mildred Pratt, to collect oral histories from Black community members. Thomas is working on adding more oral histories to the collection stored at the McLean County Museum of History. He also organizes educational panels for the museum for occasions like Juneteenth and Black History Month. He recently had an article accepted for publication by the Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society about Black musicians in safe spaces in Bloomington-Normal from 1940-2000 that featured some of the oral histories he collected.

This fall, he’s excited to begin teaching as a TA for professor Marc Hertzman for HIST 104: Black Music. He hopes to incorporate the showmanship he learned as a musician to create compelling lectures for students.

Though he doesn’t play music professionally anymore, his home office is half library, half music studio. When he needs a break from his studies, he heads over to his drums. He remains passionate about the history of blues and thinks his dissertation topic will likely focus on Chicago blues.

Right now though, he’s just enjoying being a student and wants to soak in the educational experience as much as possible. His favorite part of life as a graduate student are the seminar classes, which he describes as feeling like a “really cool book club.”

“I just wanna enjoy being here” he said. “Being in school, being present in the moment, because I know what the work world feels like. I’ve done it for 20 years. I know what it’s like to sing for your supper. So I’m enjoying this, you know, this comfort of being at school and learning.”