In the 1950s, the Arabian American Oil Company (Aramco) partnered with the Harvard School of Public Health (HSPH) to conduct medical research on the eye disease trachoma. Aramco spent over $2 million on the project with the goal of developing a vaccine. In her new book, Disorder and Diagnosis: Health and Politics of Everyday Life in Modern Arabia, professor Laura Frances Goffman uncovered this history, which she compares to the Tuskegee syphilis experiments.

“Like their colleagues in the United States, such as those who carried out the infamous Tuskegee syphilis experiments, Aramco-Harvard researchers used nonwhite and disadvantaged populations for medical research and withheld information from them,” she writes in the book.

Trachoma is a bacterial eye disease that can lead to blindness. It is often spread by close personal contact and flies spreading discharge from the eyes or nose of an infected person. Unsanitary living conditions that lack running water often exacerbate the spread of the disease as people cannot clean their face or hands. It is a disease that is treatable with antibiotics, but if the environmental conditions remain the same it has a high reinfection rate.

Children are more susceptible to the disease and the Trachoma Project designed the research around the local women and children who visited Aramco's health facilities and clinics in local villages. The women thought they were receiving care for their children. Instead, researchers collected eye scrapings from the patients but did not provide treatment.

In the early days of the project, when they were still trying to isolate the specific bacteria that causes trachoma, researchers intentionally infected five blind children with trachoma and other viruses to compare the clinical and laboratory results, Goffman recounts in the book.

Despite how easy the disease is to treat and proven methods of prevention, researchers remained committed to developing a vaccine and used the project to justify withholding treatment and neglecting village sanitation. In contrast, doctors and researchers who contracted trachoma while working received treatment and sanitary living conditions.

The Trachoma Project and other Aramco funded projects, like the use of insecticides to combat malaria, were intended to target diseases perceived as detrimental to local people's ability to work, Goffman explains.

The experiments lasted until the 1970s. Goffman reports that over three thousand people, including infants and young children, received experimental vaccines, but a vaccine was never successfully developed—although the experiments built the careers of the scientists who worked on the project.

The history of the trachoma experiments is little known. Goffman uncovered it by reading oral history transcripts of Aramco doctors and following the trail of their scientific papers. She suspects this history is not unusual and that there are more examples of using disadvantaged people to conduct medical experiments in the name of scientific progress around the world during this time.

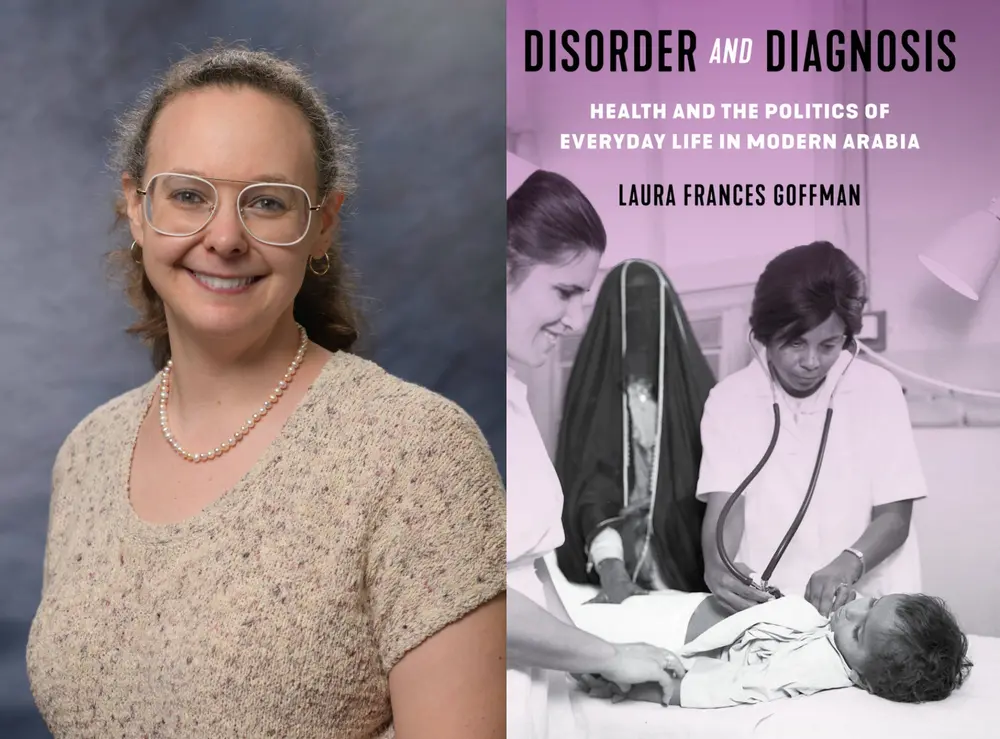

Her book Disorder and Diagnosis: Health and Politics of Everyday Life in Modern Arabia is a history of how medicine, disease, and public health transformed the Persian Gulf Coast from the late 19th century until the 1973 oil boom. In addition to the trachoma experiments, she also explores the ineffectiveness of quarantine stations built by the British, the popularity of hospitals, local women’s response to the medicalization of childbirth, how migrant Arab women nurses in Kuwait built their medical system, and how folk medicine continued to coexist alongside biomedicine. The medical projects she covers illustrate how the region “served as a buffer zone between ‘diseased’ Asia, the Ottoman Empire, and white Europe,” she writes in the book.

Throughout, she emphasizes the role of local people in their history and includes people who are usually overlooked in the larger historical narrative.

“So often the history of this region and the contemporary politics are told through a series of decisions made by elite men, whether it's local elites, corporate oil executives, or British imperial officials. I saw working on health and disease as a way to counter that,” she said.

She also centers women and their experiences with public health in the region.

“The politics of health are the perfect space to demonstrate how the choices women make every day as women, as workers, as citizens, as mothers, as caretakers, as nurses, as doctors and all these different types of roles, these decisions are very political and in turn go on to have a big impact on the way that the politics and economy of the region unfolds,” she said.

She hopes the book spurs further work on the history of medicine and health in this region and that historians continue to uncover the stories of people who are often overlooked and don’t always appear in the archives.

Goffman joined the Department of History in Fall 2023 and teaches courses on Middle Eastern history.