The Tārīkh al-fattāsh was long thought to be a sixteenth century work that chronicles the West African Songhay Empire (1464-1591). However in his previous book, Sultan, Caliph, and the Renewer of the Faith: Aḥmad Lobbo, the Tārīkh al-Fattāsh and the Making of an Islamic State in Nineteenth-Century West Africa (Cambridge University Press, 2020), history professor Mauro Nobili proved that the chronicle was actually a nineteenth century forgery produced by rewriting a seventeenth century text, the Tārīkh ibn al-Mukhtār. The rewritten chronicle was created to provide legitimacy to the Caliphate of Ḥamdallāhi (1818-1862).

He also shows how the Chronique du chercheur, previously considered the definitive scholarly edition of the Tārīkh al-fattāsh, was actually a conflation of the nineteenth century Tārīkh al-fattāsh with the seventeenth century Tārīkh ibn al-Mukhtār.

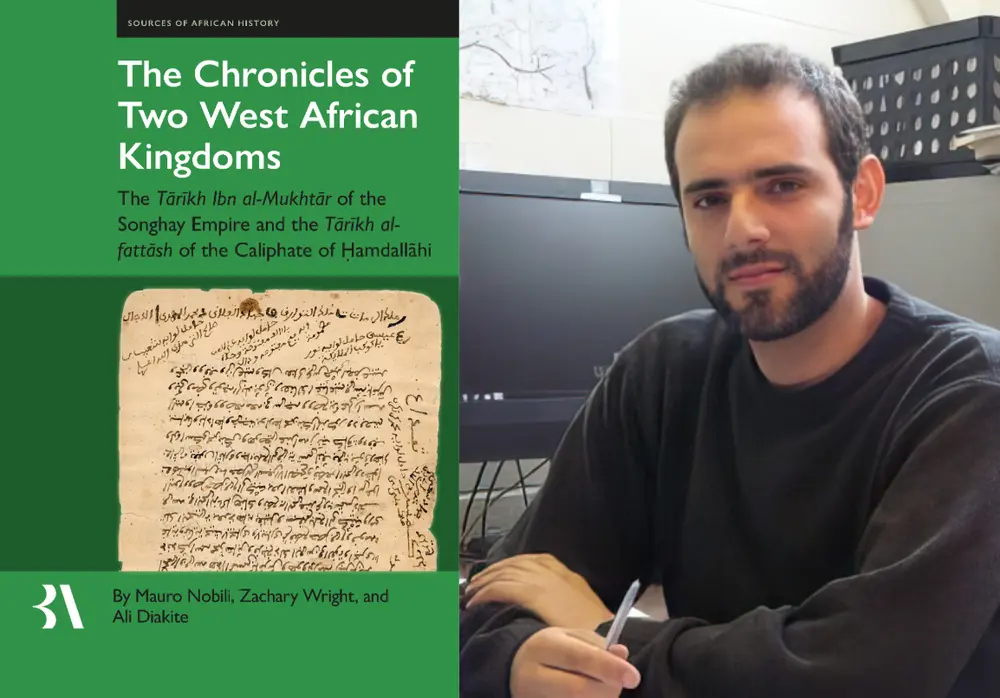

In his new book, The Chronicles of Two West African Kingdoms: The Tārīkh Ibn al-Mukhtār of the Songhay Empire and the Tārīkh al-Fattāsh of the Caliphate of Ḥamdallāhi, Nobili and co-authors Zachary V. Wright, and H. Ali Diakité untangle the two historical works and provide the first accurate English translation of both texts along with three interpretative essays and a critical Arabic edition of both works. They show how these works highlight the pivotal role of Muslim scholars in pre-colonial West Africa. Read on for a Q&A with Nobili to learn more about the book.

Tell us about the Tārīkh Ibn al-Mukhtār. What is its central argument and what does it reveal, or obscure, about the Songhay Empire?

The chronicle, even in its problematic rendering of the 1913 edition in which it is conflated with the Tārīkh al-fattāsh, has often been see as a simple political history of the Songhay Empire – and at times as an act of political nostalgia. Instead, the Tārīkh Ibn al-Mukhtār is a 17th century philosophical reflection on leadership, produced in a time of crisis, namely after the empire’s fall in 1591. Ibn al-Mukhtār argues that government succeeds when it is just, and justice comes from following Islamic ethical principles which are best represented by independent Muslim scholars. Therefore, rulers should honor, support, and honor scholars without controlling them, because scholars embody piety and moral authority.

How does your approach to interpreting the Tārīkh Ibn al-Mukhtār differ from previous scholars?

Apart from the argument I made above, our new edition, in which scholars can for the first time in about two hundred years read the Tārīkh Ibn al-Mukhtār in its original text, corrects several misinterpretations of pre-1600 history of West Africa. For instance, it demonstrates that evidence used to describe forms of slavery and servitude in the Middle Niger at the time of the so-called empires of Mali and Songhay are in fact passages introduced in the nineteenth century and that racial discourses underpinning such practices did not exist prior the 1800s. Furthermore, the polished text finally allows for a reconstruction of Songhay statecraft that was obscured by later layers of writing. For instance, the structure of the state emerges very clearly. There were two main governmental regions, respectively governed by the “viceroys” - the Kourmina-fari and the Dendi-fari – who were the second in command after the king, who constantly moved between different royal residences that served as footholds to run his incessant military campaigns. Such campaigns were at the very basis of the Songhay administration, in a fashion that seems to have been quite common in African history, like in the cases of Borno or the moving capitals of Ethiopia and Buganda.

Tell us about the Tārīkh al-Fattāsh and why it was created to legitimize the nineteenth century Caliphate of Ḥamdallāhi.

The caliphate of Ḥamdallāhi was founded by a scholar from today’s central Mali called Aḥmad Lobbo. In 1818, he led a revolution in the Middle Niger that contested the religious establishment of the region and overthrew the local military elites. More broadly, his revolution marked a significant shift in the relationship between religious and political authority. Aḥmad Lobbo broke with the traditional distance that scholars maintained from rulers—a stance Lamine Sanneh calls “political neutrality.” In the new caliphate, political legitimacy rested on the ruler’s religious authority, creating a state where governance and Islamic scholarship were indissolubly intertwined. In other words, the caliph of Ḥamdallāhi was, as French historian Bernard Salvaing put it, “the new man” of the Middle Niger and as such his legitimacy was contested by several local actors.

Here enters the long-forgotten author of the Tārīkh al-fattāsh, Nūḥ b. al-Ṭāhir, advisor to Aḥmad Lobbo. He composed the chronicle to strengthen his patron’s legitimacy through a skillful blend of themes drawn from local historiographical traditions and broader Islamic thought.

How does your approach to interpreting the Tārīkh al-fattāsh differ from previous scholars?

Past scholars who had already spotted out some inconsistencies and anachronisms, have approached it as pollution to cleanse to restore a genuine text. I approach the history of the Tārīkh al-fattāsh’s production in a different way. Firstly, I treat it as a whole new text, and not as an original plus added interpolations. Then, I do not dismiss it due to its forged nature. On the contrary, I believe that the fact of forgery is a fascinating historical phenomenon that triggers crucial questions on the world that produced it. Hence, I use the Tārīkh al-fattāsh as a compass to navigate the history of the Caliphate of Ḥamdallāhi and, more broadly, of the intertwined histories of politics, religion, and literacy in Islamic West Africa

What do these texts tells us about the role of Muslim scholars in politics in pre-modern West Africa?

These two chronicles highlight the pivotal role of Muslim scholars in pre-colonial West Africa as intellectuals deeply engaged with the question of Islam’s place in political life. In addressing this issue, they had to navigate both the localized historical circumstances of their societies and the broader, enduring tension within Islamic history represented by the uneasy relationship between scholarly authority and political power. In doing so, the chronicles challenge earlier historiographical models that either depict scholars as entirely “neutral” or assume they were inevitably engaged in a project to seize political power, a view rooted in the Orientalist notion that Islam itself mandates such political ambition.

What myths do you hope your book will dispel or what do you hope the book will help readers unlearn?

On a general level, I hope that we can put to rest the long-held assumption that West African writers were unsophisticated, mere recorders of historical events who were devoid of any philosophy of history, political ambitions, or the ability to manipulate literary corpora for ideological purposes. Contrary to that, we demonstrate that West African writers have long demonstrated sophisticated historical interpretation and articulated philosophies of history that were put to the service their political ambitions. On a more specific level, I hope that we will once and for all obliterate the idea that the Tārīkh al-fattāsh is a genuine 16th century chronicle that can be cherry picked to extract historical data. On the contrary, the latter is a sophisticated forgery written in the 19th century and tells us something about the tumultuous century that predates colonialism; while the historian interested in pre-1800 West Africa history needs to look into the reconstituted Tārīkh Ibn al-Mukhtār, which is a complex work of history composed in the second half of the 17th century.