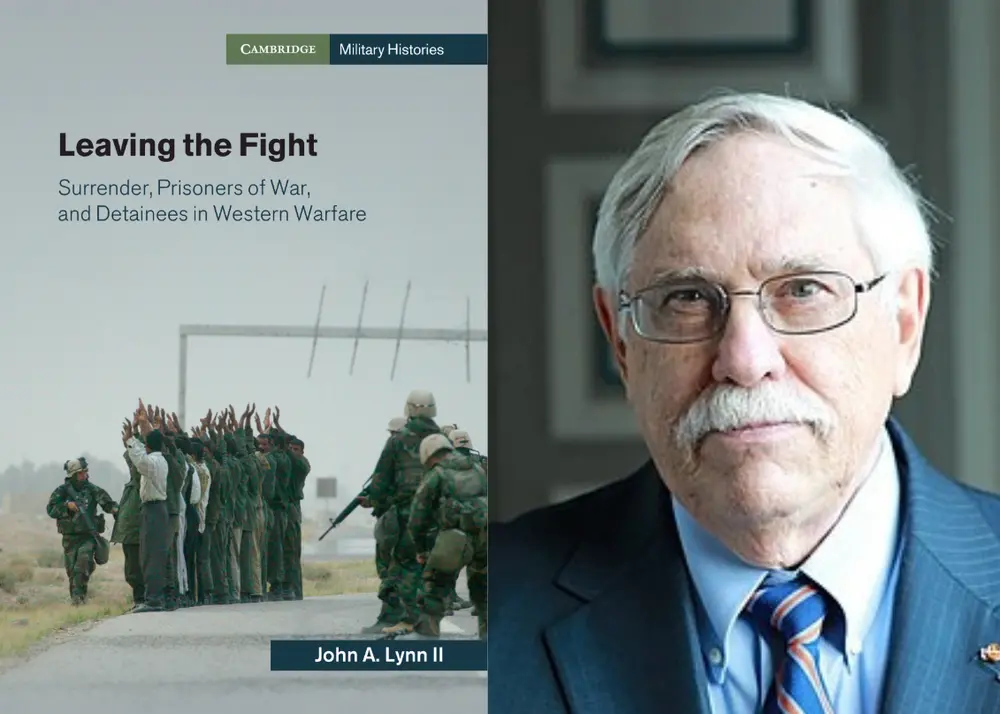

Leaving the Fight: Surrender, Prisoners of War, and Detainees in Western Warfare, a new book by emeritus professor of history John A. Lynn II proposes a novel approach to exploring the evolution of surrender in the West from the Middle Ages to the present. He examines surrender and the treatment of prisoners of war as an ever-evolving aspect of war that reflects and defines the nature of society, culture, and conflict.

“As important as they are, the subjects of surrender, prisoners of war, and detainees have rarely been addressed as general phenomena in warfare. Certainly, specific surrenders during particular wars have been discussed at length. Consider for example, Appomattox. But we lack a broad ranging comparative literature,” he writes in the book. “It is hoped that my book will simply be one more link in a much longer chain of study and discovery.”

In the book, Lynn breaks surrender down into five different categories: state declared surrender, state de facto surrender, armistice or cease-fire, surrender of military forces ends fighting, and withdrawal.

He also looks at the four consequences of surrender: acquiescent surrender by states and societies, state surrender as a hiatus in a longer serial conflict, surrender as a source of resentment, resistance, and revanchism in societies, and surrender as a transformation into another kind of war.

We spoke with him about a few aspects of his book: how the ending of the American Civil War was a transformation into another kind of war, the treatment of prisoners of war and civilian detainees over time, and how state surrender shifted after 1945.

How did you choose the conflicts you cover in your book?

I believe that the study of surrender in Western warfare should begin with the Middle Ages. Surrender and the taking and treatment of prisoners of war takes a crucial turn at that point, and from then on one can trace an evolution over the following centuries. That evolution can then be detailed through a series of conflicts. My emphasis is on the evolution over time, and only centers on specific wars from the American Civil War on. Granted my book has an American emphasis, and from that perspective the Civil War is essential.

You use the American Civil War as a key example of how surrender can be a transformation into another kind of warfare, and the ways in which warfare and surrender shape and define culture. Can you tell us more about that?

Americans generally believe that the surrenders of 1865 brought an end to the Civil War with a Northern victory. But I argue that Southern convictions of white supremacy ultimately caused of the war. And after defeat in the conventional fighting in 1865, the war turned into an insurgency and terrorist campaign in the South, as fought by the KKK and other groups. With the withdrawal of Federal forces from the South in 1877, the South achieved a political, social, and cultural victory for white supremacy. Thus, the South ultimately won the Civil War.

How were prisoners of war treated during the Middle Ages?

During the late Middle Ages, the surrender of military elites through the act of surrender, the payment of ransom by the prisoners, and the granting of parole to captured members of the elite (so they could collect the ransom they owed) were accepted as honorable alternatives to being killed in battle. These practices were extended to all men in battle, commoners as well as elites, with the ruler both collecting ransoms and paying them for those who fought in the ruler’s forces.

During the mid-seventeenth century through the first half of the nineteenth century adversaries would form “Cartels”, which were agreements to regulate ransom, exchange, and parole practices. How did this practice change during the American Civil War?

Early in the American Civil War, the Union and the Confederate governments agree to a cartel that was clearly modeled on eighteenth-century cartels. When the Union put African American soldiers into the ranks, the Confederates refused to recognize them as prisoners of war when captured. This led the Federals to sharply curtail earlier patterns and confined all prisoners of war in prisoner of war camps without the possibility of exchange or parole. Thus, the practice of long-term confinement became the fate of prisoners, and it would remain so in Western warfare for all parties to conflicts, with some exceptions.

Why did civilian detainees increase after the Korean War?

After the Korean War, counterinsurgency roped in high numbers of civilian detainees who were suspected of being insurgents, their supporters, or sources of information valuable to counterinsurgents. Such practices were followed in the Vietnam War, but became particularly key in the Afghanistan War, 2001-2021, and the Iraq War, 2003-2011.

After World War II ended with the unconditional surrenders of Japan and Nazi Germany, and the US and USSR entered the Cold War, surrender by withdrawal became more prevalent in western warfare. Why?

After 1945 the major states, US and USSR, fought proxy wars of intervention. Since the commitments to intervene were political exercises, when events came a cropper, the intervening power could react to its defeat by simply withdrawing. US surrenders in Vietnam and Afghanistan were surrenders by withdrawal. The dangers of nuclear made a major war between the US and the USSR mutual suicide.

One of the messages of your book is that surrender on the state, unit, and individual levels reflects and defines the nature of society, culture, and conflict. How does the end of the war in Afghanistan reflect and define US culture?

The Afghanistan War reflected American shock after 9/11. So US troops invaded in October of 2001. But, after the Allied invasion of Iraq in 2003, the fighting in Afghanistan became a back-burner war, still hot but not center stage. When the Taliban, who had been expelled by early 2002, returned to the offensive in 2006, the US responded, but we were behind the curve, with so much invested in Iraq. Even a surge in Afghanistan, 2010-2011, failed to turn the tide. It became a question of holding on and hoping the Afghan government could raise the forces and the capacity to take over. But this was not to be. The American public tired of the war, and the administrations of Trump and Biden stepped back from expectations of success. The Americans were at first dedicated to the destruction of al Qaeda and those who sheltered this radical Islamist group. The invasion of 2001 was a matter of justice and revenge, but the lack of a clear victory eventually wore down American resolve. In 2021 we surrendered by withdrawal, a pullout that turned to chaos with Taliban success.