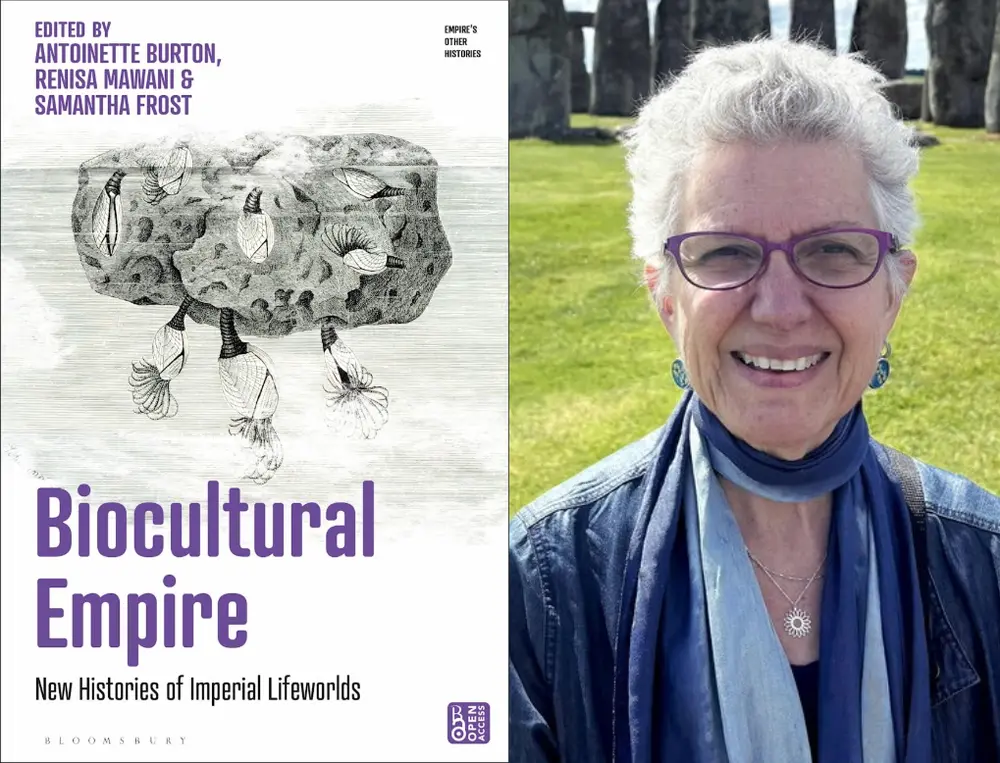

History professor Antoinette Burton recently published Biocultural Empire: New Histories of Imperial Lifeworlds, a collection of essays that she co-edited with Renisa Mawani and Samantha Frost. Their edited collection asks what histories of empire look like when the species supremacy of humans is questioned rather than assumed. Read on for a Q&A with professor Burton about the collection.

What was the inspiration behind the creation of this edited collection?

Over ten years ago I attended a talk given by Samantha Frost, a co-editor of this volume and a professor of political science at Illinois, called “Biology for Humanists.” She cast the lecture as a set of challenging arguments about the relationship between nature and culture. The talk was really smart, though frankly there was a lot that puzzled me about it, and some things I just didn’t understand at all. I felt like she was speaking a different language. I asked to meet Sam for coffee so she could help me figure it out. That developed into months of conversations and sharing of work, and fierce debates about history and humanism and narrative and method and audience. It resulted in my deep investment in the idea that humans are “biocultural creatures.”

As I began collaborating with a colleague at the University of British Columbia, Renisa Mawani, on a project about the nonhuman worlds of the modern British empire, I introduced her to the book Sam published out of this work, Biocultural Creatures: A New Theory of the Human, in 2016. Renisa was as intrigued as I was, and the three of us decided to join forces and organize a collection of essays by historians of empire that put the biocultural at the center of inquiry. Thus idea for Biocultural Empire the book was born.

What does it mean to interpret history through a biocultural framework and how does it help us rethink histories of empire? Can you provide an example?

Although many scholars of empire are interested in its environmental histories, most don’t start from the premise that the human and nonhuman worlds were (and are) entangled. Our book is an effort to make those connections clearer, and to show what that entanglement looked like both metaphorically and in actuality. My contribution to the volume shows how the blurring of lines between human beings and creatures like birds, horses, scorpions was everywhere to be seen in political cartoons and other visual forms at some of the most intense moments of 19th century British imperial history. That interspecies imagery was allegorical, reflecting how embedded knowledge of the biocultural was in metropolitan culture. In contrast, Debjani Bhattacharyya’s essay illustrates the direct consequence of the nonhuman on how imperial power functioned. Her research focuses on how the silt from the Bengal Delta made its way so deeply into the legal infrastructure of the British empire in India that it materially impacted revenue collection and the wider economy of the Raj. “Muddy water” was no metaphor, but an active agent of biocultural change on the ground in one of the most significant nonwest regions to be shaped by modern imperialism.

How does a biocultural framework connect to an anticolonial view of history and the work of Indigenous, Black, and scholars of color?

As many of the contributors suggest, the intellectual and political traditions drawn on by contemporary Black, Indigenous, and Métis scholars who have taken the biocultural for granted as a cosmological approach to the world anticipated our work by centuries. One of the aims of the collection is to contribute to making these ways of knowing more visible in British imperial history, which remains largely focused on human agency rather than the work, ideological and embodied, of an assemblage of lifeworlds. Sylvia Wynter, Alexis Pauline Gumbs, Robin Wall Kimmerer, Zoe Todd – these are scholars with whom British empire historians need to reckon if they want to begin to interrupt the existing narratives of how and under what conditions imperialism not only took root, but was challenged or thwarted by biocultural forces underfoot.

What myths do you hope your book will dispel or what do you hope the collection will help readers unlearn?

Our hope is that readers will see more clearly how the quest for white supremacy that underwrote imperial ambition was connected to a belief in species supremacy – the conviction that dominion over the land, the sea, and the plants and animals therein was an indispensable part of imperial success. At the same time, that porous boundary-line could make imperial possessions and colonial settlements unstable and even ungovernable. Whatever the case, those who have experienced imperial history in place clearly know that they are living in biocultural conditions. We hope the research in our collection brings that knowledge to the fore and becomes an integral part of how we study and teach British imperialism.

How do you hope to see a biocultural framework evolve in British imperial history?

The examples that the contributors to this collection have explored are the tip of the iceberg when it comes to understanding exactly how, why and under what conditions imperial lifeworlds were lived in a biocultural mode. We hope scholars will use Sam’s book as a touchstone and surface more evidence of the inseparability of human and nonhuman ecologies, and that the biocultural as she has mapped it will begin to shape how students of empire think about its past – and its present.