Even though Richard Young is pursuing his PhD in history, he has always been interested in computers. During his undergraduate years, Young and his friend, a computer science major, would get together over weekends to tell each other what they were learning about in their respective fields of study.

“We always complained that it felt like the other had picked the right major,” said Young.

Both were fascinated by the overlap between history and technology, leading Young to learn how to code. After receiving his bachelor’s in history from the University of California, Davis, he taught himself several programming languages.

As a graduate student at the University of Illinois, Young takes an unconventional approach by researching the history of happiness through advertisements. His dissertation begins in the 1890s, when he argues advertising became “professionalized in such a way that they were using psychological knowledge in the advertisement.”

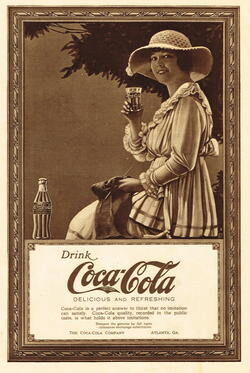

This approach, he says, “gets pronounced in the 1920s and ’30s, when advertisers became aware of the social effects they’re having.” Young focuses on how emotional appeals shaped early 20th-century advertising, especially in companies like Coca-Cola. But to trace emotion at scale, he emphasizes the need to “look beyond Coca-Cola to a broad range of material, which is impossible to do manually.”

To tackle this, Young uses AI programming to analyze representations of happiness not only in text, but also in images, films, radio, and other media. Many of these sources, he explains, “have these messages about happiness,” and through AI, he can detect emotional patterns across massive collections.

One example is the “Coca-Cola Girl,” known for her iconic smile in decades of advertisements. Young states that when analyzing advertisements such as this, he must train AI to “recognize a smile.” He explains further, “I can’t just find the word ‘happy.’ I have to use digital tools if I want to find what I’m looking for.” After AI detects these visual cues, Young must determine how people in the 20th century interpreted those gestures and their context.

Young emphasizes that the reach of advertisements, such as those by Coca-Cola, has far deeper implications than we often realize. Coca-Cola’s advertising extended beyond print images to include radio, television, and even film endorsements, such as in “Doctor Strangelove.” According to Young, we often overlook the pervasive influence of advertising historically.

Young decided to take his interest in integrating technology and history further by joining SourceLab, the University of Illinois’ digital humanities collective. Professor John Randolph, the director of SourceLab, offered Young a position as a research assistant after they discussed his interest in digital humanities. Young leads students and faculty in exploring various digital humanities tools in their weekly meeting, SourceLab Mondays.

Being part of a community of digitally inclined historians helped him see how important it is to get historians interested in the field of digital history.

“I very much like the idea of using computers to help with my historical work, and I've found it's a hard sell to a lot of historians. Finding a community where there’s interest in that has been very helpful and very valuable,” Young said.

Outside of his role at SourceLab, Young finds fulfillment in collaborating with his advisor, Teri Chettiar, whose expertise in the history of emotions closely complements his research. Reflecting on his motivation for pursuing a PhD, he shares, “If I could get paid to do research my entire life, I would be very happy.” While he hopes to become a professor, Young remains open to a range of career possibilities. Ideally, he’s looking for a role that intersects his technical skills with his passion for history.

by Eva Grein