The Midwest played a central role in the growth of Black freedom movements in the 20th century. It was a key site for incubating and expanding the ideas of political activist Marcus Garvey, not only in the U.S., but globally, said University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign professor of African American studies and history Erik S. McDuffie.

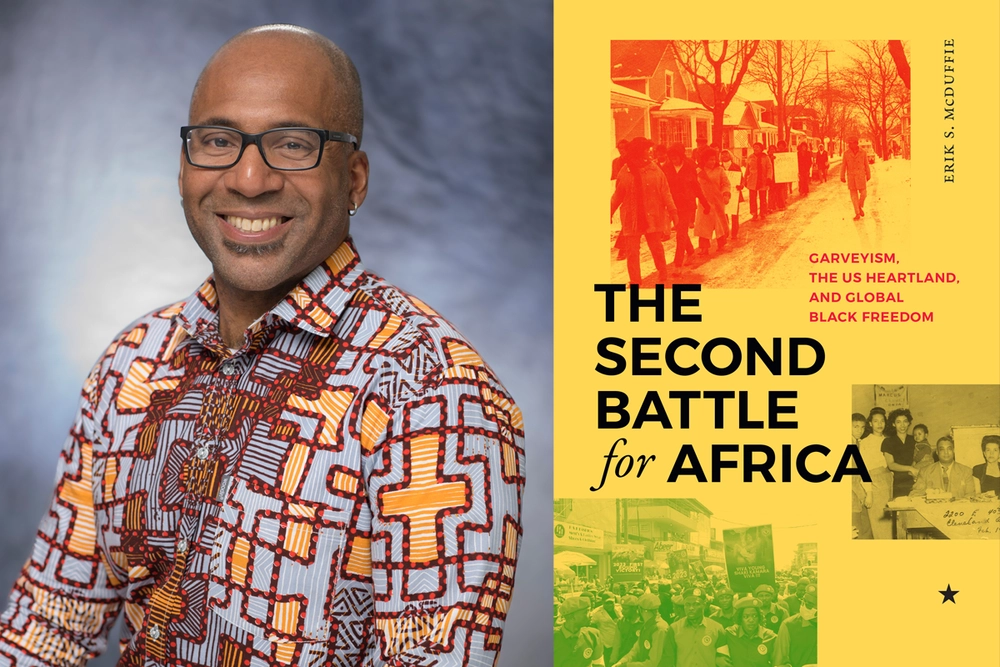

McDuffie examined the influence of Garvey and the importance of the Midwest in the growth of Black internationalism and radicalism in his new book, The Second Battle for Africa: Garveyism, the U.S. Heartland and Global Black Freedom.

McDuffie said the book is deeply personal and tied to his family history and Midwestern roots. He grew up in suburban Cleveland in a family that was interested in history, politics and global events and that hailed from St. Kitts, Canada and the U.S. His great-grandfather was a Garveyite who once introduced Garvey at a 1923 Detroit rally.

Garvey, who grew up in Jamaica around the turn of the 20th century, campaigned for the self-determination and autonomy of Black people, the end of colonial rule in Africa, race pride and connections between Africa and the African diaspora. His ideas emerged at a time of global upheaval following World War I. He founded the Universal Negro Improvement Association, which claimed 6 million members worldwide in the 1920s and was the largest Black protest movement in history at that time.

“Garveyism is the most potent social, political, cultural and spiritual force in the Black world from the early 20th century forward. So many movements, formations and institutions across the African world — not just the Midwest and the U.S., but in the Caribbean, Africa and beyond — directly or indirectly were inspired by Garveyism,” McDuffie said. “You can’t talk about Black people in the 20th century without talking about Garvey.”

The Midwest was particularly suited for its role as a hub of Black political activism, McDuffie said. He described the region as “the dialectic of opportunity and oppression.”

Black people viewed the North as a promised land where they could be free from slavery. They could vote. Midwest cities were manufacturing centers, with automobile plants, steel mills and rubber plants bringing millions of people from around the world to work in those industries. Black men could earn higher wages than they could find elsewhere, McDuffie said.

“What makes it distinct is the way Black people found unique political and economic opportunities that they couldn’t find anywhere else in the world,” he said.

Their political and economic power helped make the UNIA branches in Midwestern cities some of the largest and most influential in the world, with Chicago, Detroit and Cleveland particularly important, McDuffie wrote. Chicago became the site of Johnson Publishing Company and Third World Press Foundation, important publishers of Black literature, magazines and news, and Malcolm X College.

At the same time, the Midwest was the site of virulent racial oppression and violence, with lynchings, Ku Klux Klan activity, laws restricting the freedoms of Black citizens and a white settler colonialism perspective, McDuffie said.

“These forces came together, and then Garvey was talking about race pride, self-determination and a free Africa. It helped radicalize Black people in unique and important ways,” he said.

The politics of some Black nationalists embraced Black settler colonialism in Africa, anticommunism, capitalism and heteropatriarchy. They at times collaborated with white supremacists on their common ground of separation of the races and colonization of Liberia for Black people who wanted to live freely in Africa, McDuffie said.

While some of Garvey’s ideas leaned toward the right wing, they transcend the ideological spectrum of Black thinking, McDuffie said. Many activists inspired by Garvey rejected those ideas for more leftist views.

“Most people appreciated how he inspired pride, encouraged them to build institutions and advance autonomy, and his anticolonial message,” McDuffie said.

Women played a critical role in grassroots community work and in leadership roles in the UNIA, and they promoted the empowerment of Black women. McDuffie wrote about the influence of Louise Little, the mother of Malcolm X who was born in Grenada and later lived in Nebraska and Michigan. She was instrumental in cultivating a Black radical perspective in her children and laid the foundation for the work of Malcolm X, who maintained a lifelong connection to the Midwest, particularly Detroit, McDuffie said.

He also wrote about James Stewart, who succeeded Garvey as UNIA president-general and moved its headquarters to Cleveland, then later to Liberia. Garveyism inspired independence campaigns in Africa and the Caribbean. It inspired new movements, including Rastafarianism and the Nation of Islam, which was founded in Detroit. Garveyism also was critical to shaping the Civil Rights and Black Power movements, McDuffie said.

The continuing impact of Garveyism is seen today in the field of African American studies, which was established as the result of activism in the 1960s and ‘70s, and in the Black Lives Matter movement, he said.

“It’s not accidental that Ferguson, Missouri, and Minneapolis were the sites where Black Lives Matter truly went global, given the unique intersections between opportunity and structural violence against Black people,” McDuffie said. “There’s a tendency among scholars to erase the Midwest when talking about the global African diaspora. I really want to emphasize the importance of the Midwest in shaping 20th-century Black life.”

Editor's note: This story originally appeared on the University of Illinois News Bureau website.